-40%

Chinese N. Song Dyn. Jade Ink Stone with Tortoise (Bixi) & Dragons + Translation

$ 8712

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

ANCIENT CIVILIZATIONSArtifacts, Antiques, & Fine Collectables

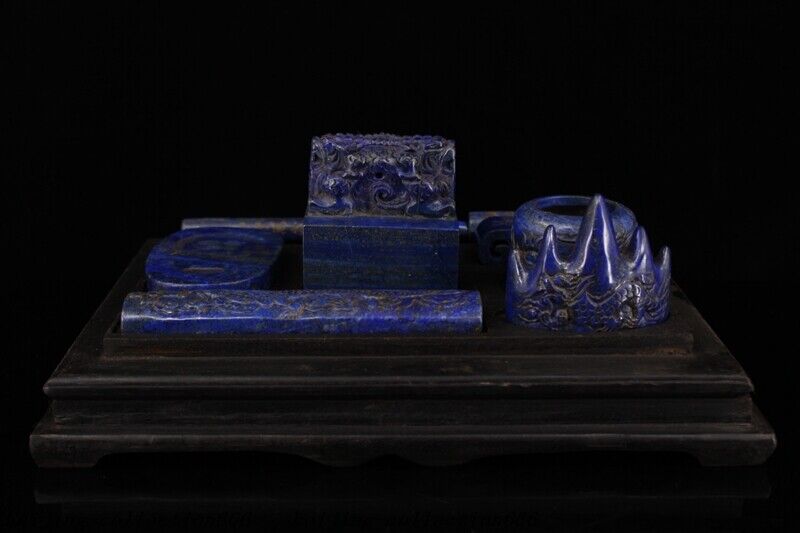

Chinese Song Dynasty Jade Ink Stone with Tortoise (

Bixi

)

Ink Stones are one of the “Four Treasures of the Study”

Dragon & 30+ Characters with English Translation

Northern Song Dynasty

c. 960—1170 A.D.

NOTE:

William D. Houghton, the President of ANCIENT CIVILIZATIONS

, a State of Washington Licensed Business,

assumes all responsibility for the information contained in this description and for the English translation and transcription of the ancient Chinese graphic characters.

Furthermore, I prohibit the further dissemination of this information in any written, video, or electronic format without my expressed, written approval.

Thank You!

Summary

Item:

Chinese Jade Tortoise Inkstone

Material:

Black nephrite jade with celadon & orange highlights and inclusions.

Inscription: An estimated 30+ pictograms/characters incised and percussively pecked into the jade amulet.

Country:

China

Culture:

Northern Song Dynasty

Est. Date:

960—1170 AD

Approximate Measurements:

·

Width:

7.56” (192mm)

·

Height:

2.72” (69mm)

·

Depth:

2.64” (67mm)

·

Weight:

2.185 lb. (990gr)

Condition:

This nephrite jade inkstone is in exceptionally good condition with no repairs or restorations.

The inkwell does show old mineral deposits (likely from the calcium & iron in the water) from ancient use. The one-piece, black jade inkstone has moderate inclusions of celadon-green and one end that is also a stunning shade of celadon.

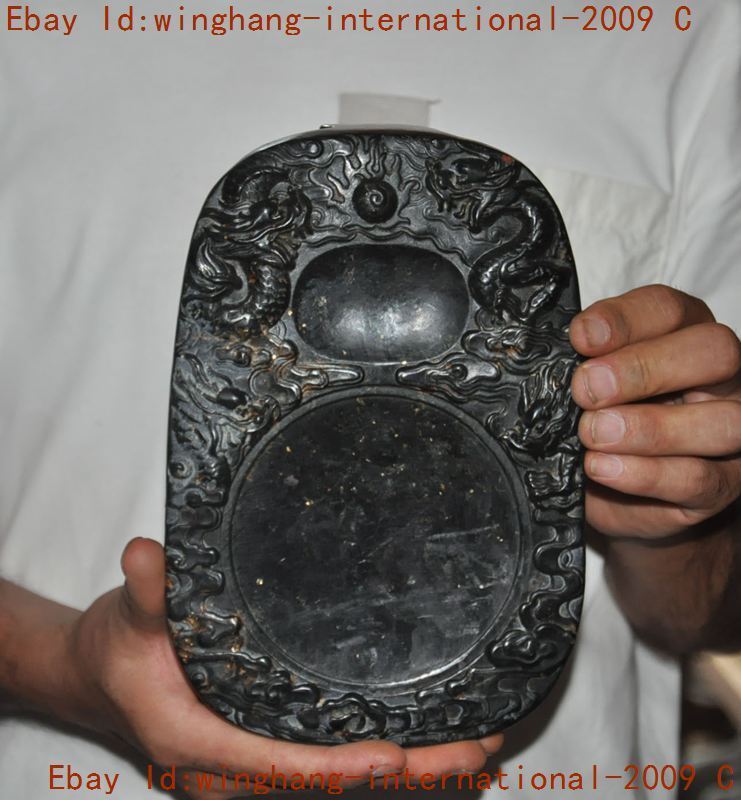

This solid nephrite jade inkstone is about 7.56” (192mm) in length and features an Earth Tortoise on one end that symbolizes the belief that the Earth was supported in the sky by large tortoises.

On the opposite end, there is a raised, rectangular box that contains the concave inkwell and a cutout that held water.

There are two, scrolled feet on each end of the inkstone to support it—a style that was popular in the 10

th

to 12

th

Century AD in China.

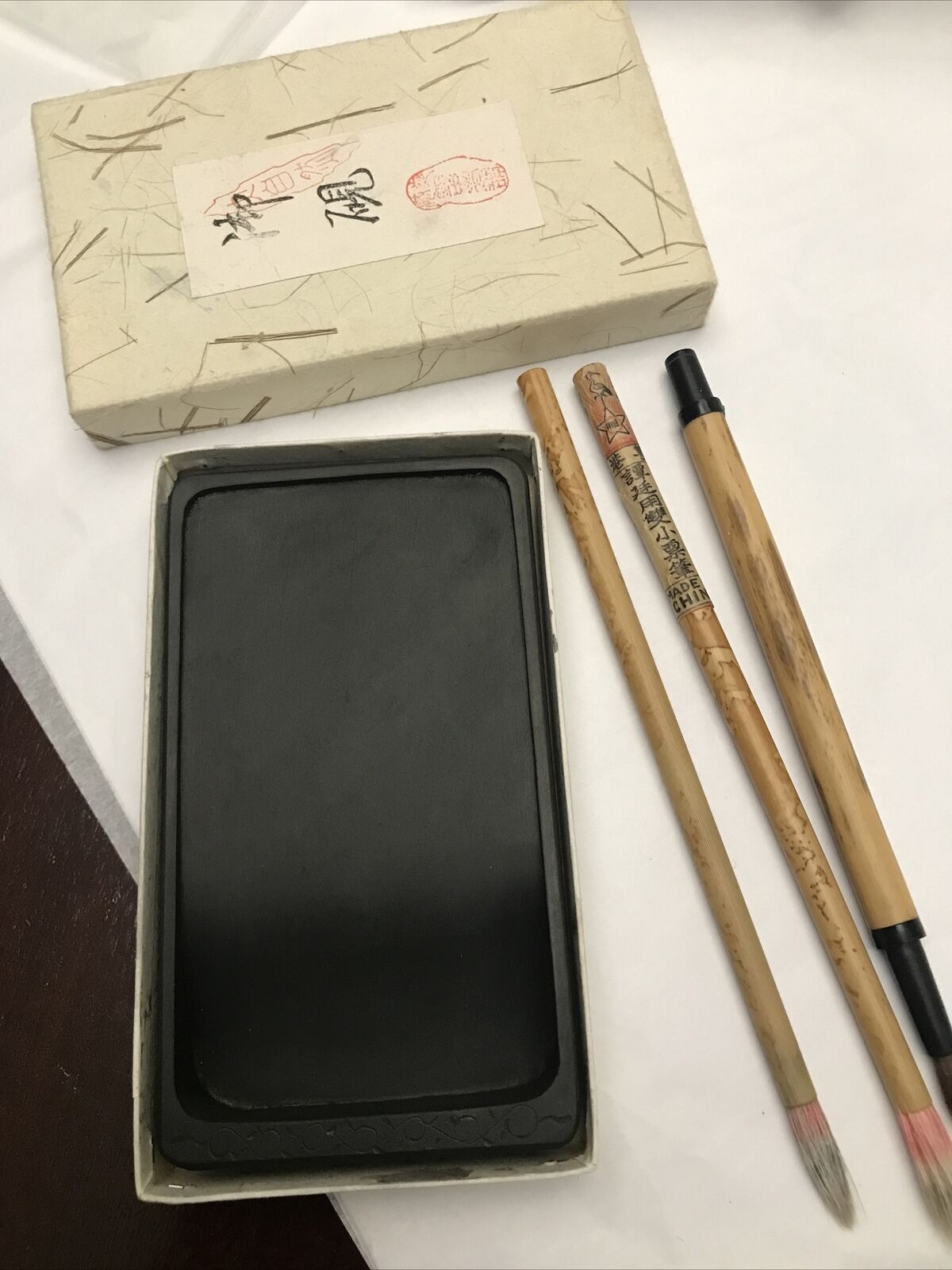

Historically, inkstones were considered one of the “

Four Treasures of the Study

”—the others being brush, ink, and paper—that were used by ancient Chinese scholars, royal officials, and emperors for millennia.

This stunning jade inkstone would have been owned by an upper-class mandarin or official who had great power within the emperor’s realm.

The production of high-quality, jade accessories by imperial stonemasons and craftsman was extremely limited to imperial aristocrats.

There are approximately four pictographic images of Fire-Breathing Dragons incised and percussive pecked into the jade inkstone—one small enough to fit on the surface of the Tortoise’s left eye!

This Dragon incredibly only measures about 7.5mm or .30” in length.

WOW!!!

{See Photos 6-7.}

In addition, there are an estimated 30+ other characters pecked into the inkstone.

{See details and English translation below.}

Archaeologists have discovered jade inkstones among other grave goods in tombs of the Liao (907–1125), Yuan, and Ming (1368–1644) dynasties. Although these inkstones are prized for the lustrous beauty of the stone, they are less practical for calligraphers due to the less-than-optimal way in which the ink interacts with the surface of the jade as opposed to the more efficient inkstones made from clay or other stones. Consequently, these pieces have been used more often as ornamentation in scholarly studios.

NOTE:

All items offered for sale by Ancient Civilizations are unconditionally guaranteed authentic. They were legally imported to the United States years ago and are legal to sell and own under U.S. Statute Title 19, Chapter 14, Code 2611, Convention on Cultural Property.

DETAILS

This jade inkstone measures 7.56” (192mm) in length x 69mm in height x 67mm in depth, and it weighs a very substantial 2.185 lbs. (990gr).

Chinese inkstones are one of the “Four Treasures of the Study”, which also include

brush, ink, and paper, that were used by ancient Chinese scholars, artists, calligraphers, royal officials, and emperors for millennia.

A carved turtle, known as

bixi

, was used as a plinth for memorial tablets of high-ranking officials during the Sui Dynasty (581-618 CE) and the Ming periods (1368-1644 CE).

Auction prices for

inscribed, jade

Chinese inkstones have exceeded .5 million USD in recent auctions! Why such steep prices?

Jade has traditionally been the imperial stone of China and has symbolized the omnipotent power of the emperor.

Although other stones and clay were used to make inkstones, it is the jade examples that were treasured accessories by the emperors of ancient China.

This museum quality jade inkstone that features a tortoise on one end, was made about 1,000-years-ago from a single block of black nephrite jade with green highlights and inclusions.

It was likely made by a several craftsman who worked for the imperial palace during the Northern Song Dynasty (960—1170).

The making of inkstones, the palette on which artists and calligraphers grind solid sticks of ink with small drops of water to make the inks before applying them to paper or silk, which reached its epitome during the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1170 A.D.) with the Emperor Song Huizong at its forefront. In fact, contemporary Chinese scholars, artists, and calligraphers still use inkstones in the making of ink, as the consistency and quality of the ink utilized is such a critical element in how the ink flows from the brush and is absorbed by the paper medium.

Since ancient times, Chinese calligraphers have utilized brushes, ink, paper, and inkstones as essential writing accoutrements in their studios. These tools have undergone various stages of use and development throughout China's dynastic history; they represent the means by which Chinese culture has been transmitted and the scholarly foundation of the Confucian culture of East Asia.

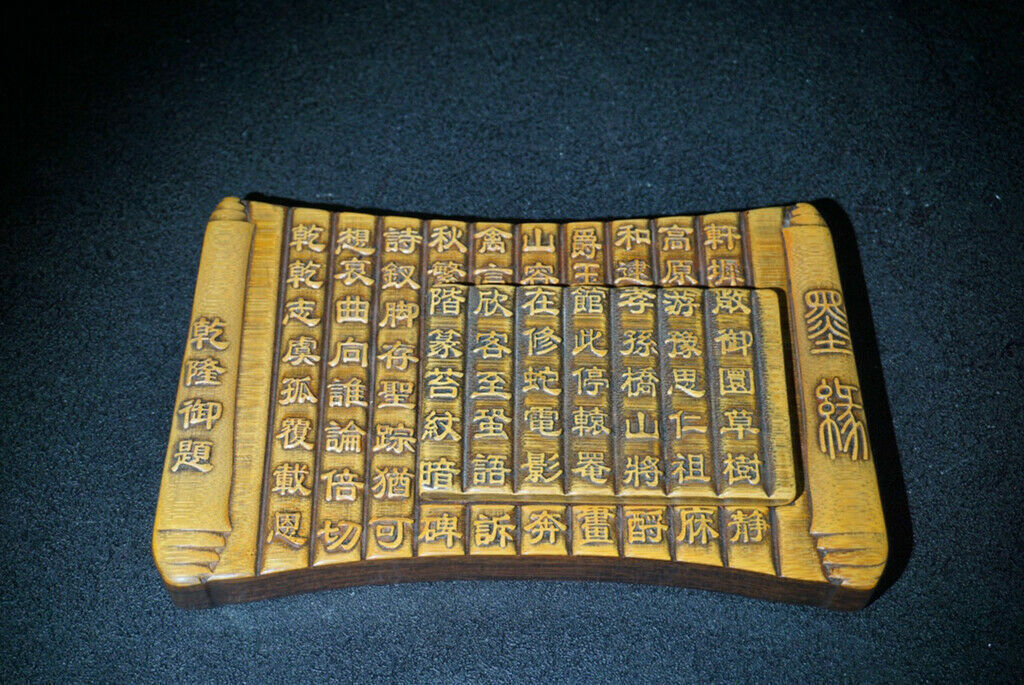

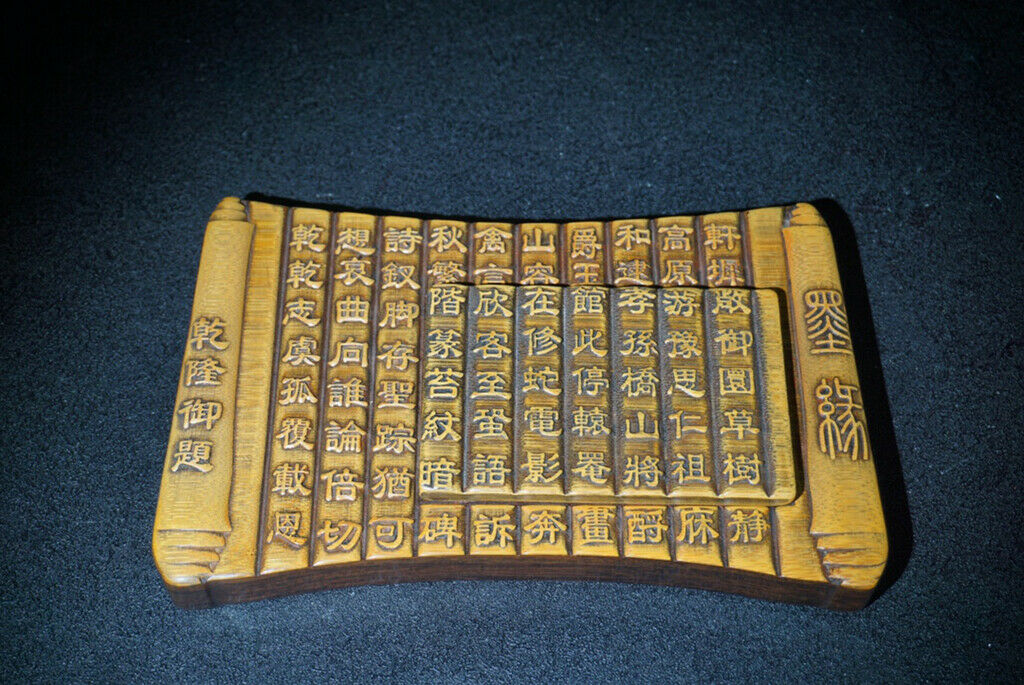

TRANSLATIONS OF PICTOGRAPHIC CHARACTERS

Note:

I assume all responsibility for the information contained in this description and for the English translation and transcription of the ancient Chinese graphic characters.

Furthermore, I prohibit the further dissemination of this information in any written, video, or electronic format without my expressed, written approval.

Thank You!

There are approximately 30+ pictographic characters that have been incised and percussively pecked into the hard nephrite jade.

Several of the characters are to faint, but here are some of the ones I can see clearly enough for me to translate into English:

The largest character can be found on the underside of the jade inkwell—a Dragon.

He measures about 3.8” (97mm). {See photos # 11-12.

He is facing right, and I’ve drawn a red box around him.

You can see the individual percussive pecked marks (seen as orange from the iron in the damp soil where it was buried for about 1,000 years) that were used to outline the shape of the omnipotent Dragon, including his horns/ears and his open mouth that is breathing Fire (highlighted inside a white circle)!

There are much smaller figures of the Sons who are making offering to the Ancestors, who are also shown.}

The smallest character is also a Dragon and this one can be found incised into the left eye of the Tortoise—I’ve drawn a blue circle around him, and you can see him facing left.

This Dragon incredibly only measures about 7.5mm or .30” in length!

{See photos # 6-7}.

This Dragon is incised, likely with a piece of flint that has been flacked to an ultra-fine point.

It was only meant for the eyes the Ancestors, as human eyes were not worthy to see it.

On the left side of the Tortoise’s shell there are several characters.

Inside the red circle, there is the character of a Grandson holding a skein of yarn, which symbolizes generations of descendants.

Inside the white box, there is a Son who has sacrificed an animal.

There are perhaps 12+ other smaller characters on the Tortoise’s shell.

{See photo # 8.}

There are four characters on each of the corners surround the round inkwell (that also symbolizes Heaven (Tian).

I can not see them clearly enough to make a positive translation, but I suspect they are the four directions of the Earth—North, South, East, and West.

The tortoise is one of the "

Four Fabulous Animals,

" the most prominent beasts of China. These animals govern the four points of the compass, with the Black Tortoise the ruler of the north, symbolizing endurance, strength, and longevity.

{See photo # 4.}

On one end of the inkstone, there is the pecked image of an ox that I’ve drawn a blue box around.

He is facing left (you can see his two curved horns) and appears to have been sacrificed to the Ancestors by the Sons with flint axes, as you can see the individual pecked marks that symbolize the blood from the ox.

{See photo # 9.}

On one side, there is the figure of a cat/tiger like animal facing right, with his tail high up in the air.

{See photo # 10.}

And there are approximately another 25+ characters that are too faint or abstract for me to translate.

BRIEF HISTORY OF CHINESE INKSTONES

Since ancient times, Chinese calligraphers have utilized brushes, ink, paper, and inkstones as essential writing accoutrements in their studios. These tools have undergone various stages of use and development throughout China's dynastic history; they represent the means by which Chinese culture has been transmitted and the scholarly foundation of the Confucian culture of East Asia.

By traditional Chinese definition, hardstones are divided into two categories: jade, which is the mineral nephrite, and all other precious and semi-precious stones. Jade is considered the most esteemed gem of all and associated with many desirable qualities in humans.

Jade Inkstones

The art of sculpting inkstones from jade began in the Han dynasty and was developed throughout Chinese history. These inkstones are fashioned from a variety of green, white, and black jade. The Song-dynasty artist Mi Fu (1051–1107) wrote of an inkstone he personally sculpted from green jade.

Archaeologists have discovered jade inkstones among other grave goods in tombs of the Liao (907–1125), Yuan, and Ming (1368–1644) dynasties. Although these inkstones are prized for the lustrous beauty of the stone, they are less practical for calligraphers due to the less-than-optimal way in which the ink interacts with the surface of the jade as opposed to the more efficient inkstones made from clay or other stones. Consequently, these pieces have been used more often as ornamentation in scholarly studios.

Jade inkstones of the Qing Dynasty were made primarily in the Imperial workshops, and certain antique pieces were inscribed in the Jiaqing Reign to denote how they were personally appreciated by the Jiaqing Emperor.

Traditional East Asian ink is solidified into inksticks. Usually, some water is applied onto the inkstone (by means of a dropper to control the amount of water) before the bottom end of the inkstick is placed on the grinding surface and then gradually ground to produce the ink.

More water is gradually added during the grinding process to increase the amount of ink produced, the excess flowing down into the reservoir of the inkstone where it will not evaporate as quickly as on the flat grinding surface, until enough ink has been produced for the purpose in question.

The Chinese grind their ink in a circular motion with the end flat on the surface while the Japanese push one edge of the end of the inkstick back and forth.

Water can be stored in a water-holding cavity on the inkstone itself, as was the case for many Song Dynasty (960–1279) inkstones. The water-holding cavity or water reservoir in time became an ink reservoir on later inkstones. Water was usually kept in a ceramic container and sprinkled on the inkstone. The inkstone, together with the ink brush, inkstick and Xuan paper, are the four writing implements traditionally known as the “Four Treasures of the Study.”

The Kangxi, Yongzheng, and Qianlong Emperors personally designed some of the inkstones they commissioned. For example, the Kangxi Emperor discovered Songhua stone on one of his eastern excursions to Mukden (present-day Shenyang) and ordered it to be quarried and sculpted into inkstones. The Yongzheng Emperor also enjoyed exquisite inkstones; he participated in designing warming inkstones with copper burners. After these two emperors innovated the design of inkstones, other emperors would continue in the tradition. As an avid connoisseur, the Qianlong Emperor designed a variety of inkstones with ancient and classical styles from the Han (206 BCE–220 CE), Tang (618–907), Song (960–1279), and Yuan (1271–1368) dynasties; some of his designs originated in the inkstone catalogues of Su Shi (1037–1101) and Gao Lian (1573–1620). The Qianlong Emperor also commissioned many inkstones with inscriptions of his poetry.

Imperial archives show how much of the production of inkstones made according to ancient styles during the Qianlong period were actually overseen by officials of the Suzhou textile manufactory and other large productions sites far from the capital. Others were presented as regional tribute by governors and other high officials. For instance, the governor of Anhui presented She inkstones, and the superintendent of Guangdong Customs presented Duan inkstones. Some officials presented materials for production, as in the case of Shanxi officials presenting fine clay.

Certain inkstones are marked with the names or titles of officials or the imperial household. Those articles with inscriptions such as “Imperially Appreciated by Jiaqing” (

Jiaqing yushang

) are characteristic of the Qing Dynasty period in which they were made or show how the imperial treasury added the mark of imperial appreciation to a piece from the old palace collection. Some of the inkstones from the Daoguang period were designed with warmers to heat the ink during the cold, winter months and have inscriptions denoting the practical use of the object.

During the Jiaqing and Daoguang Reigns, the court proscribed or limited the presentation of tribute; these restrictions affected the making of new inkstones. As the era of Manchu rule waned, the production of inkstones declined. Few inkstones were made during the Tongzhi and Guangxu Reigns, and, of those made, very few are considered quality works.

The Tortoise in Chinese History

The tortoise is one of the "Four Fabulous Animals", the most prominent beasts of China. These animals govern the four points of the compass, with the Black Tortoise the ruler of the north, symbolizing endurance, strength, and longevity.

The tortoise and the tiger are the only real animals of the four, although the tortoise is depicted with supernatural features such as dragon ears, flaming tentacles at its shoulders and hips, and a long hairy tail representing seaweed and the growth of plant parasites found on older tortoise shells that flow behind the tortoise as it swims. The Chinese believe that tortoises come out in the spring when they change their shells, and hibernate during the winter, which is the reason for their long life.

The tortoise is a symbol of longevity, with a potential lifespan of ten thousand years. Due to its longevity, a symbol of a turtle was often used during burials. A burial mound might be shaped like a turtle, and even called a "grave turtle."

A carved turtle, known as

bixi

, was used as a plinth for memorial tablets of high-ranking officials during the Sui Dynasty (581-618 CE) and the Ming periods (1368-1644 CE).

Enormous turtles supported the memorial tablets of Chinese emperors and support the Kangxi Emperor's stele near Marco Polo Bridge in Beijing, China. Tortoise shells were used for witchcraft and future forecasting. There are innumerable tales on the longevity of the tortoises and their ability to transform into other forms.

In China, the traditional Chinese character symbolizing the turtle (

龜

) shows a head like that of a snake at the top, to the middle left of the paws, to the middle right of the shell, and at the bottom of the tail. According to the "

Book of Ceremonies

", the white tiger, phoenix, tortoise, and dragon are the four entities that possess spirit. Tortoise shells were used for divination during the ancient Chinese Shang Dynasty and carry the earliest specimens of Chinese writing. Some Chinese are of the opinion that their script was taken from the signs on the back of the tortoise.

For the Chinese, the tortoise is sacred and symbolizes longevity, power, and tenacity. It is said that the tortoise helped

Pangu

(also known as

P'an Ku

) create the world: the creator Goddess

Nuwa

or

Nugua

cuts the legs off a sea turtle and uses them to prop up the sky after

Gong Gong

destroys the mountain that had supported the sky. The flat plastron and domed carapace of a turtle parallel the ancient Chinese idea of a flat earth and domed sky. For the Chinese as well as the Indians, the tortoise symbolizes the universe.

The Chinese Imperial Army carried flags with images of dragons and tortoises as symbols of unparalleled power and inaccessibility, as these animals fought with each other, but both remained alive. The dragon cannot break the tortoise and the latter cannot reach the dragon. In China, the tortoise was also called the Black warrior, standing as a symbol of power, tenacity, and longevity, as well as that of north and winter. A tortoise was often put at the base of burial monuments.

Legend holds that the wooden columns of the Temple of Heaven in Beijing were built on the shells of live tortoises since people thought that these animals were capable of living for more than 3,000 years without food or water and are adorned with a magical power that prevents wood from rotting.

The tortoise is of the

feng shui

water element with the tiger, phoenix, and dragon representing the other three elements. According to the principles of feng shui the rear of the home is represented by the Black Tortoise, which signifies support for home, family life, and personal relationships. A tortoise at the back door of a house or in the backyard by a pond is said to attract good fortune and many blessings. Three tortoises stacked on top of each other represent a mother and her babies. In Daoist art, the tortoise is an emblem of the triad of earth-humankind-heaven.

And in modern times, calling someone a "tortoise" in China was considered offensive, as the tortoise does not remember the day and month of its birth so

REFERENCES:

The Great Bronze Age of China

:

An Exhibition from the People’s Republic of China

, edited by Wen Fong, 1980

Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1980.

Ancient Chinese Warfare

, Ralph D. Sawyer, Mei-chün Sawyer

Archaeology

, Archaeological Institute of America, Feb/March 2015

Shanghai Museum

British Museum

Museum of Chinese History, Beijing

China Online Museum

British Museum

Rawson, Jessica.

Chinese Jade from the Neolithic to the Qing

. London: British Museum, 1995.

Smithsonian Museum, Sackler & Freer Gallery, WDC

MET, New York

Please see photos for details as they are part of the description. Thank You!

PROVENANCE

This ink stone was obtained from a private collector who once lived in Beijing, China, and this is the first time it is being offered for sale as a set in the United States.

Bid with confidence--as I have Positive Feedback from hundreds of satisfied customers from around the world!

International Buyers are responsible for all import taxes, duties, and shipping.

No

international returns. Thank You!

Please look carefully at the photos, taken with 4x macro lens, since they are part of the description.

It

would make a

wonderful

addition to your collection or a Super gift!

The stand and the ruler are not part of the auction, just there to give you a perspective and a good view of item.

And please ask any questions before you buy.

Thanks!